Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia

Kings County, est. 350 residents

Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia, is a historic gem and an important centre of Acadian culture. The area was originally the home to the Mi’kmaq, who inhabited the land for centuries before the first Acadians arrived in the early 1600s. The Mi’kmaq and the Acadians would become close allies throughout their history as the Mi’kmaq made a vital contribution to the survival of the Acadians by providing them with knowledge of the land.

Most Acadians are descended from around 50 French families who settled in the region between 1639 and the early 1650s. While the pre-1755 Acadian families were mainly of French origin, there were a few exceptions, including individuals of Basque, Spanish, Portuguese, Irish, English, and Scottish backgrounds.

Meaning “Great Meadow” in French, Grand-Pré was founded by Acadian settlers Pierre Melanson, Marguerite Mius d’Entremont, and their children who travelled east from Port-Royal in the early 1680s. Others soon followed, and the settlement grew into a vibrant Acadian community that flourished along the rivers and shores of the Minas Basin.

While Acadians did not begin settling the Minas area until the late 17th century, the name “Les Mines” dates back to 1604. Sieur de Mons and Samuel de Champlain heard the Mi’kmaq talking about copper deposits along the shores of the Bay of Fundy and wanted to get a better look for themselves. Although the copper didn’t meet expectations, the name Les Mines stuck to the shoreline region.

Acadians began establishing extended villages along the rivers that flowed into the basin. By the early 1700s, Les Mines was the largest population centre of Acadia, with Grand-Pré being its most populous settlement. A big reason for this prosperity was the dykes the Acadians built to protect their agricultural farmland from flooding. Being so close to the Bay of Fundy, the dykes were meant to tame the high tides and to irrigate the rich fields of hay. The surplus of grain and cattle was then shipped to New England and, after 1720, to Louisbourg, the capital of Île Royal (Cape Breton Island).

Acadian traders also exchanged goods with the Mi’kmaq, the British at Annapolis Royal and Halifax, the French colonies along the St. Lawrence River, and on Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island). By doing this, Acadian traders obtained goods normally unavailable in the colony. After 1713, when the Treaty of Utrecht was signed, France signed over the sovereignty of the area where most Acadians lived to Great Britain. Acadie became Nova Scotia, and in the eyes of the British, trading surplus grain and livestock with the French colonies began to seem like trading with the enemy.

Unrest in Acadia

Despite being a thriving community, Grand-Pré was not without its complicated past. After Great Britain and France declared war in 1744, hostilities erupted in Acadia. Seemingly caught in the middle, the Acadians aimed to protect their interests by not fully committing to one side or the other. The British constantly worried about the Acadian’s increasing numbers and their refusal to take an unqualified oath of allegiance. As time went on, they became less and less understanding.

During this challenging period, French soldiers from Louisbourg passed through Grand-Pré and other populous Acadian communities. Some Acadians provided food and moral support for soldiers, while others went as far as to join the attack on Annapolis Royal. The British resented the support the Acadians had given the French and cited these actions when the decision for the Grand Dérangement was finalized.

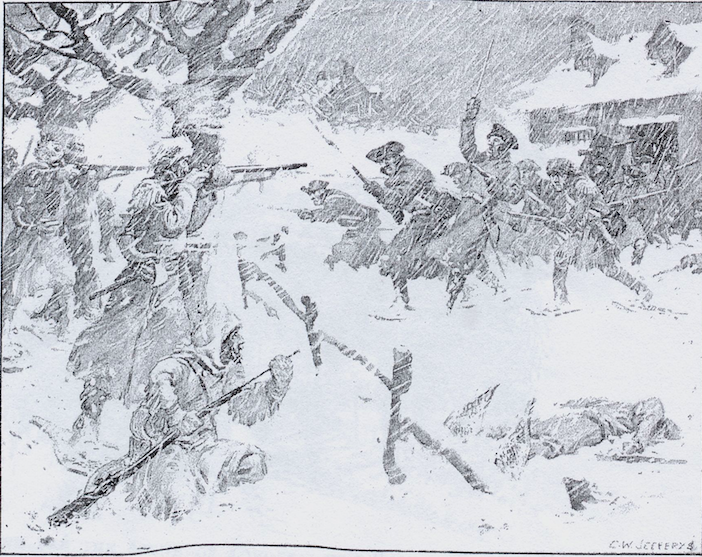

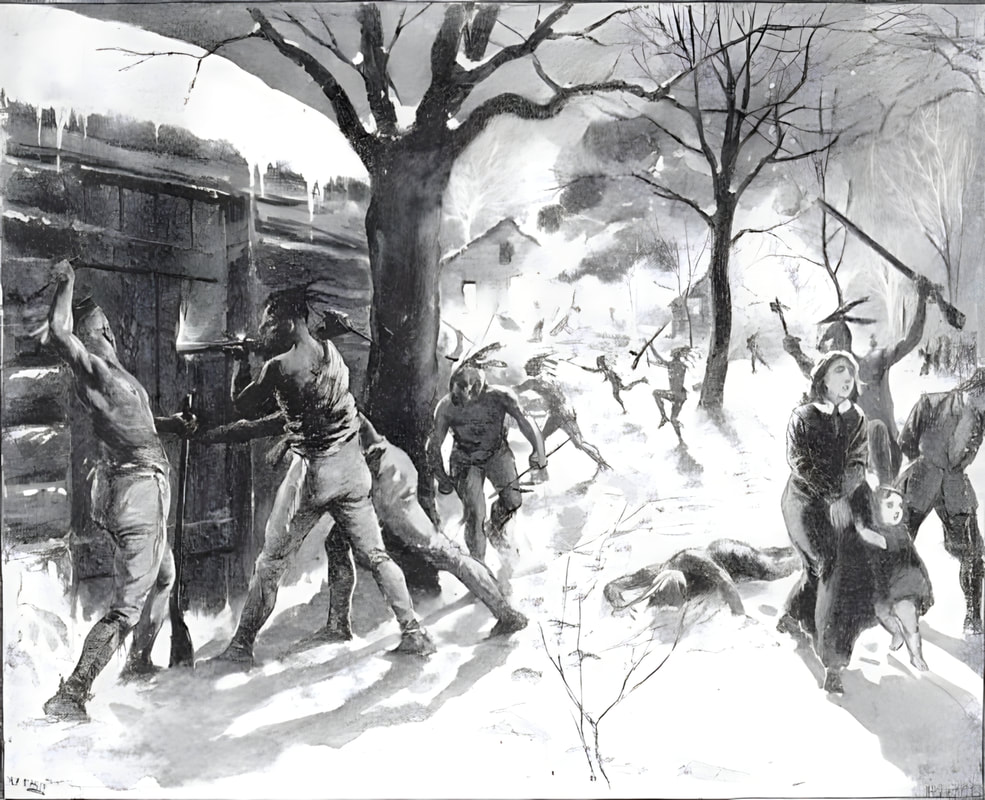

The Battle of Grand-Pré occurred in early 1747 when around 300 French soldiers and Amerindian warriors undertook a difficult mid-winter journey through deep snow and ice from the Chignecto region to the district of Les Mines. Their objective was to confront a force of 500 New England troops stationed at Grand-Pré. The New England soldiers wanted to ensure they secured the head of the Bay of Fundy and had planned to attack the French at Beaubassin in the future.

As they crossed the Cobequid district, the French and Amerindian forces took precautions to keep their destination hidden. While some Acadian militia joined the cause, there were also a handful who were not allies. The attack unfolded at night amid a blinding snowstorm, which caught the New Englanders at Grand-Pré entirely off guard. With most British soldiers asleep, the French and their Amerindian allies achieved a decisive victory, leaving the British with a bitter sense of defeat.

The Expulsion of the Acadians

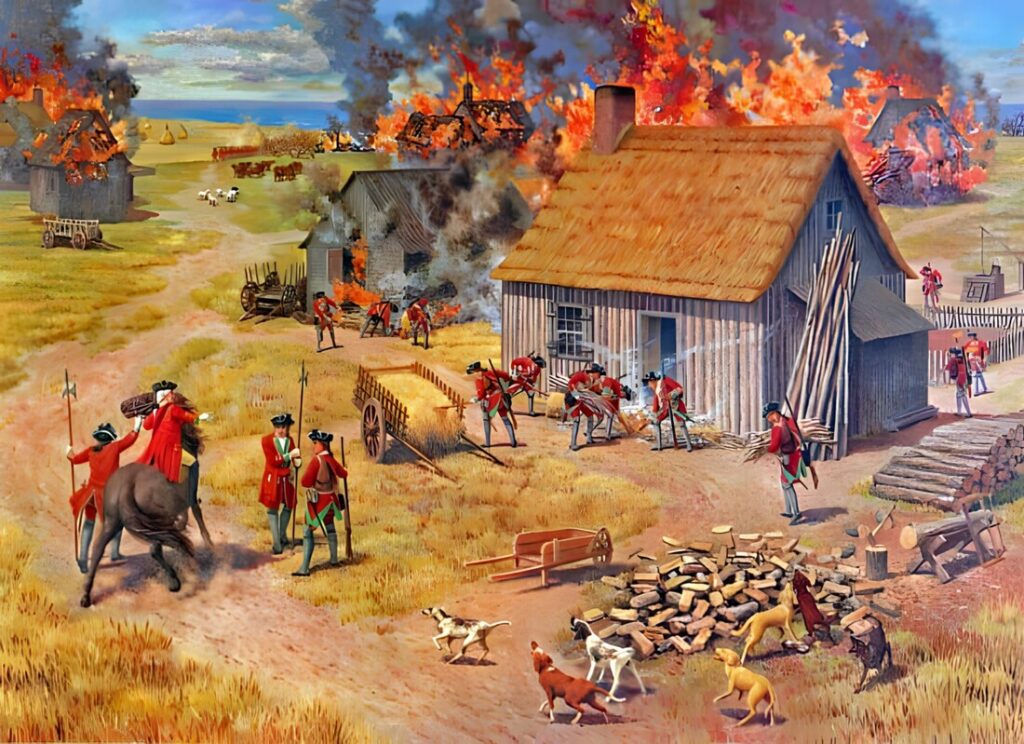

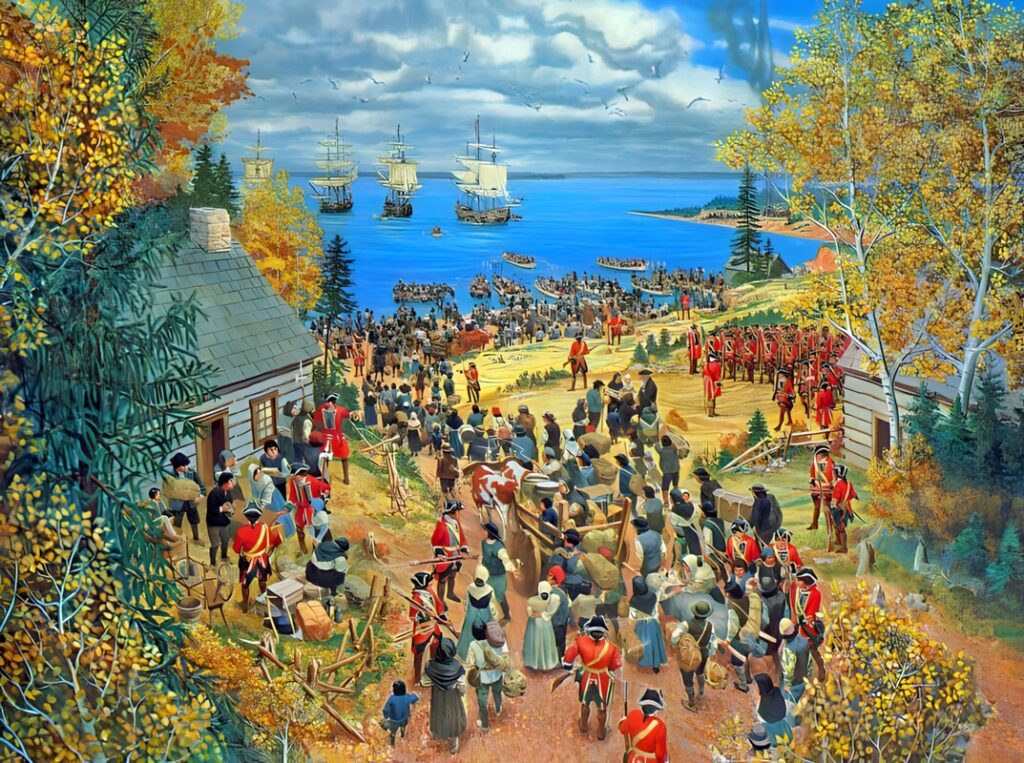

The Expulsion of the Acadians began in 1755 when British forces became sick of the Acadians’ neutrality after they continuously refused to swear an unconditional oath of allegiance to the Crown. The acting governor and the Council of Nova Scotia decided to force the Acadians to take the standard unqualified oath or be deported if they refused. The Acadian representatives refused, and due to this lack of loyalty, the British began the “Grand Dérangement.”

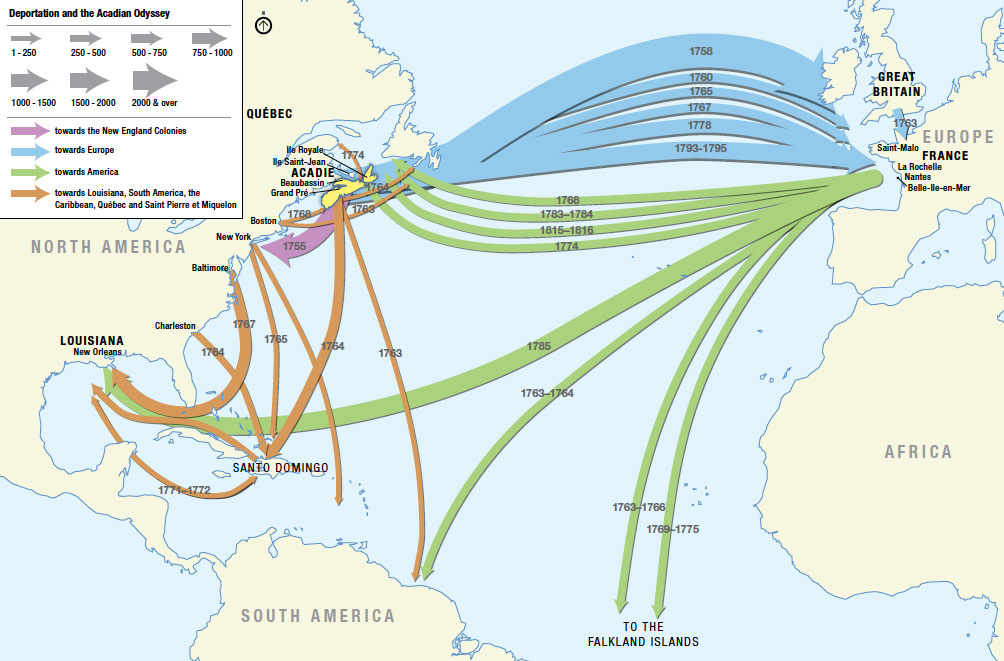

Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow from New England was in charge of the deportation from the area of Les Mines. Around 2,200 Acadian men, women and children were removed from the region, which would account for a third of the nearly 6,000 Acadians deported from Nova Scotia. Over the next eight years, over 10,000 Acadians were removed from their homes in present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island and dispersed throughout the American colonies, England and France.

Some individuals evaded deportation and even carried out a guerrilla resistance against British forces. Not wanting to leave the area they called home and in search of family and friends, many endured hunger, illness, desperate living conditions, sadness over the death of loved ones and anguish at seeing children forced to work at such a young age.

In 1764, the British permitted Acadians to return to Nova Scotia. In spite of the good news, their former lands had been settled by New England Planters during their absence. Acadians were forced to settle in different areas around Nova Scotia and other provinces like New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Québec. While this was a homecoming for some, many exiled Acadians never returned to their homeland.

Despite their efforts, the British’s attempt to assimilate the Acadians largely failed. The refugees retained their sense of identity, faith and determination to survive. Grand-Pré is particularly associated with the Grand Dérangement more than other sites due to the detailed journal kept by Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow in 1755 and its role as the setting for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie, published in 1847.

This poem became a unifying symbol for the Acadian people after it was published. The story highlights a young Acadian girl from Grand-Pré who was separated from her betrothed during the deportation and her strength to continue. Evangeline has since become more than just a fictional character; she has come to symbolize the resilience and perseverance of the Acadian people.

The Great Upheaval left its mark on three continents. It is a story of resilience in the face of adversity, and for those who returned from exile, it is a deeply moving testament to their unwavering connection to their ancestral lands. Today, there are an estimated three million descendants of Acadians worldwide. The Atlantic provinces, Québec, Louisiana, New England and France, have the largest Acadian communities, but other traces can be found in Haiti, the Falkland Islands, and Belize.

Grand-Pré Today

The Grand-Pré National Historic Site was created to commemorate the Acadian settlement that thrived in the region between 1682 and 1755. In 1907, John Frederic Herbin purchased most of the land believed to be the site of the church of Saint-Charles-des-Mines so that it could be protected. The following year, the Nova Scotia legislature passed an act to incorporate the Trustees of the Grand-Pré Historic Grounds. Herbin placed a stone cross at the site to mark the cemetery of the church, using stones from what he believed to be the remains of Acadian foundations.

In 1917, Herbin sold the property to the Dominion Atlantic Railway on the condition that Acadians be involved in its preservation. The railway made numerous investments in developing the park and promoting the history of the Acadians, as it had become a staple for tourism traffic and was conveniently located beside the railway’s main line. Gardens were added to the site, and a small museum depicting the Acadians’ history was opened. In 1920, the Dominion Atlantic also erected a statue of Evangeline that was started by Candian sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert and finished by his son Henri after his death.

A memorial church was constructed when the railway deeded a piece of the land. The exterior of the church was finished by November 1922, and the interior in 1930, on the 175th anniversary of the Deportation. While the church has gone through many changes through the years, it continues to be a historical location that many visit while in Grand-Pré.

When railway tourism started to decline in favour of subsidized highway construction, the Dominion Atlantic sold the park to the Government of Canada in 1957. After the Canadian Parks Service took over the site’s operation, it was designated a National Historic Site in 1982 on the 300th anniversary of the arrival of the first Acadians in the region in 1682. In 1995, the site and surrounding area were established as the “Grand-Pré Rural Historic District National Historic Site” in honour of the rural cultural landscape, which features one of Canada’s oldest land occupations and uses patterns of European origin.

The Landscape of Grand-Pré was designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in June 2012. From the top of View Park, you can take in over 1,300 hectares of fields, marshes and dykelands that make up the unique topography. UNESCO determined that the Landscape of Grand-Pré encompasses exceptional cultural characteristics that are important to present and future generations of all humanity. The Grand-Pré National Historic Site is at the heart of the Grand-Pré Landscape and is recognized for its outstanding universal value.

The Tangled Garden is a mystical oasis and a must-stop destination in Grand-Pré. Beverly McClare opened the acre-wide garden thirty years ago after blending together her love for art, food and hard work. During the summer, the greenspace is the perfect place to view stunning flora, enjoy a spot of tea or try some of the delicious creations from the garden.

Just Us! Coffee is Canada’s first fair trade and organic coffee roaster. The business was established in 1995 with a small roastery in New Minas before quickly outgrowing that location and opening up its current home in 2000. Founded by Jeff Moore along with Debra Moore, Jane Mangle, David Mangle and Ria Dixon, the business is now owned by 17 Worker Members, meaning that workers who run the day-to-day operations are the ones who also own the company.

Before transforming into a coffee shop, the building was a local farmers market called Mr. Fresh Farm Market. Today, the Just Us! team offers freshly roasted coffee, tasty baked goods, and various organic, locally sourced treats to satisfy any craving.

Grand-Pré is renowned for its rich history and stunning landscapes. The area symbolizes the Acadian people’s resilience and heritage, continuously attracting visitors from around the world who come to reflect on its profound significance.

A big thank you to Keely from Just Us! Coffee Roasters for providing me with more information about her business.